As I write about pioneers in the American West, I think a lot about women’s perspectives on leaving their homes and setting off on the journey along the Oregon Trail. On my blog, I’ve written about specific women—Narcissa Whitman, Jessie Benton Fremont, Elizabeth Dixon Smith, Keturah Belknap, and others—and quoted some of their words, but these posts don’t focus on how they felt about making the trek in the first place. That’s one theme in my books Lead Me Home and Forever Mine. For the most part, women did not want to leave home. They only went because their husbands or fathers insisted.

In my novels, one woman is pregnant with her ninth child. She left her family’s farm in Missouri to follow her husband’s wanderlust. This woman’s teenage daughter mourns the loss of the friends she left behind. Another woman in the wagon company is accompanying her bully of a husband who believes he’ll have a better life—while her life is likely to be harder in Oregon. Another character who lost all her children in Illinois left their graves behind her forever. On and on the women’s stories go. Each mourns people and places they will never see again.

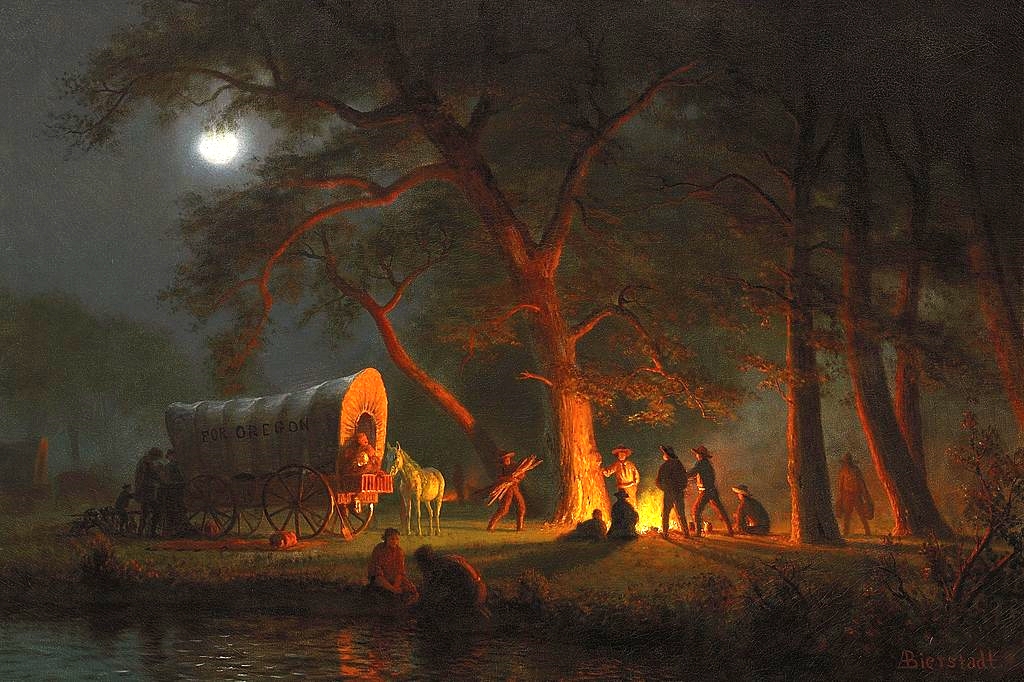

As they travel, these women cooked over campfires instead of in ovens. They made their meals with limited provisions and what they could glean along the trail. They washed with river water almost as muddy as their dirty clothes, unless they had the time to let the water sit and settle. Their family members suffered illnesses such as cholera or yellow fever or pneumonia. Or they were injured in wagon or gun accidents. Or they drowned or were snake-bit or suffered some other calamity.

No wonder the women viewed the land so harshly. No wonder some of them went mad.

Elizabeth Markham was one such woman. On September 15, 1847, as they traveled along the Snake River, Elizabeth told her husband Samuel she would not go on any farther. After some argument, Samuel took their five children and their wagons and left her behind. Later in the day, he sent their son John back to get his mother. Hours later, Elizabeth caught up to the wagon—alone. She said she had beaten John to death with a rock. Her husband went back for the boy. Stories vary as to whether she had injured John, but he lived. Samuel brought his son back to the rest of the family, only to find that Elizabeth had burned one of the wagons.

The rest of the story is that the Markhams’ traveling companions put out the fire, and the family did reach Oregon. They later had two more children. Their youngest child, Edwin Markham, became an acclaimed poet. The Markhams ran a store in Oregon City, but Samuel and Elizabeth later divorced, and Samuel set out for California alone. Elizabeth also later moved to California, remarried, and was divorced again.

Like her youngest son, Elizabeth was also a poet—the first published woman poet in Oregon. She had a poem published in the Oregon Spectator on June 15, 1848, less than a year after her episode on the Snake River. It reads:

A Contrast in Matrimony

The man must lead a happy life,

Free from matrimonial chains,

Who is directed by a wife

Is sure to suffer for his pains.Adam could find no solid peace,

When Eve was given for a mate,

Until he saw a woman’s face

Adam was in a happy state.In all the female face, appear

Hypocrisy, deceit, and pride;

Truth, darling of a heart sincere,

Ne’er known in woman to reside.What tongue is able to unfold

The falsehoods that in woman dwell;

The worth in woman we behold,

Is almost imperceptible.Cursed be the foolish man, I say,

Who changes from his singleness;

Who will not yield to woman’s sway,

Is sure of perfect blessedness.

Her note at the bottom of this poem in the newspaper read: “To advocate the ladies’ cause, you will read the first and third, second and fourth lines together.”

[Try it . . . The first stanza then reads:

The man must lead a happy life,

Who is directed by a wife

Free from matrimonial chains,

Is sure to suffer for his pains.]

This isn’t great poetry, but I have to marvel at the way she crafted two poems in one. And I have to wonder what Elizabeth was thinking as she wrote this multi-faceted poem—to which view of marriage did she subscribe? After her experiences on the Oregon Trail, did she think man better off with a wife or not? Given that both her marriages ended in divorce—still uncommon during her lifetime—I conclude she was fairly sour on the institution of matrimony.

What do you think of Elizabeth Markham’s poem?

Theresa is the award-winning author of historical fiction about settling the American West. Before she turned to writing, Theresa was an attorney, mediator, and human resources executive.

Follow Theresa on her website, https://TheresaHuppAuthor.com, or on her Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/TheresaHuppAuthor.